From place to place and from style to style Karol Szymanowski was a straussian romantic, an expressive impressionist and a folklorist – each of them at a different moment.

That did not, however necessitate searching for a language – as for a language, he had always been a master of his own one, enabling him to say exactly what he wanted to say. The journey was more one of constant search for inspirations and challenges, ways of reaching perfection suitable at a given moment.

Having reached the summit and explored its every crevice, Szymanowski went on. Thus, he had wandered from his family’s Tymoszówka estate in Ukraine, where he had been born in 1882, to Berlin – through, or rather in spite of, having studied with Noskowski in Warsaw, arriving at strauss, as was the case with most of his searching peers. Susequently, having wandered across Sicily and the Maghreb, having soaked with fascination with archaic Mediterranean cultures, he arrived at an impressionism of his own, yet with stronger hues of the East’s misticism and expression than ones of Paris’s elegance.

Eventually, discovering the charm of archaisms in his own land, he turned to the Gorale folklore of the Podhale region, reaching for other Polish regionalisms as well. What lay ahead might have been an individual neoclassicism – and what would it have been even further ahead? We will never learn, the year 1937 – the last attack of tuberculosis – finished the fascinating journey.

Sławny kompozytor polski w Kopenhadze,

w: K. Szymanowski, Pisma muzyczne, s. 462.

– 'Do you like jazz music?

– Not hot jazz. But except for that, jazz music is sometimes wonderfully beautiful.'

Sławny kompozytor polski w Kopenhadze, in: K. Szymanowski, Pisma muzyczne, p. 462.

'The violin concerto, with Paweł’s aid, I have finished […]. – I must say I am most contented with the whole – various new notes again – and at the same time some return to the old. – The whole is terrificly fantastic and unexpected.'

Szymanowski’s letter to S. Spiess, 27.08.1916, in: K. Szymanowski, Korespondencja, vol. 1, PWM, Kraków 2007.

'It has always occurred to me, that in its essence there is but one face to the true culture of the human spirit; that too hastily had we become accustomed to the schematic distinction between the culture of the mind

in science and the culture of the feeling in arts. [...] For, is not science, in the undoubted sphere of its creation, the most elevated of the arts? [...]

On the other side – art in its heights [...] is it not indeed the most beautiful

of sciences, [...] the task of which is not only to awaken a spontaneous rupture of admiration and movement, but

also an objectively justified assessment of those values that a given work of art brings with itself?'

Przemówienie Doktora Karola Szymanowskiego [while accepting his honorary doctorate from the Jagiellonian University], in: K. Szymanowski, Pisma muzyczne, p. 311.

'[…] in principle, every single human is actually a born musician, for music is, to an extent, an unchangeable function of certain psychological properties, a constant […] expression of his individual lyricism.'

Wychowawcza rola kultury muzycznej w społeczeństwie, in: K. Szymanowski, Pisma muzyczne, p. 280.

'Dearest Karol,

You know, or, it actually seems, you do not know, how crazy an admirer of your music I am, and that e.g. Symphony No. 3 and the Violin Concerto were among the most intensive sensations in my life, yet it seems to me that in the Stabat you reached even higher, unsormountable peaks, one is virtually smashed with the absolute perfection of the ingenious thing...'

Anna and Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz to Karol Szymanowski in Edle, Stawisko 12.01.1929, in: K. Szymanowski, Korespondencja, vol. 3, pt 2, Kraków 1997, p. 41.

'Bach, Beethoven, Chopin. They were the companions of my childhood. That is surely where the secret of their influence on me lies. [...] as a young boy, I felt improbable contempt for operatic music. That’s amusing. Today, I highly value Verdi.'

Rozmowa z Karolem Szymanowskim, in: K. Szymanowski, Pisma muzyczne, p. 436.

'I even write poems myself. I only began producing them at a mature age. Yet I shall burn them all, without exception, before I die!'

Rozmowa z Karolem Szymanowskim, in: K. Szymanowski, Pisma muzyczne, p. 437.

'Every one of us, among the hard, exhausting professional activity in the city, by means of magic tricks cheating their miserable budget, puts aside the few pennies, to eventually, having laborously scrambled for a few days off, quietly sets off for Zakopane. There, such a gentleman, with a smile on his face and rosy cheeks, with his eyes aglow, wanders filled with joy among snows of white and [...] is happy to – at certain moments – the extent of feeling the secret, silent and remote happiness of hermits [...]'

List do przyjaciół w Zakopanem, in: K. Szymanowski, Pisma muzyczne, p. 374.

'[...] it would be in vain for us to seek in the domain of other fine arts that comonness

and directness of influence which is specific to music.'

Wychowawcza rola kultury muzycznej w społeczeństwie, p. 129.

'I know not whether we are a nation of great or mediocre musicality. From the richness and beauty of our folklore, one would rather need to infer that we have not been able to exploit our inherent – let us say: potential – musicality to a sufficient degree.'

Wychowawcza rola kultury muzycznej w społeczeństwie, p. 133.

'Music is a mighty weapon in the fight against backwardness and barbarity of the masses a significant spiritual food, allegedly containing the greatest amount of vitamins nutritious and therefore the most likely to penetrate the deepest layers of population.'

Wychowawcza rola kultury muzycznej w społeczeństwie, p. 134.

'The viewpoint of music as a drug begins ever more clearly to yield to the outlook on it as a nutrient creative vitamin.'

Wychowawcza rola kultury muzycznej w społeczeństwie, p. 138.

'The history of humanity is actually a history of its art. It is somehow a secret light, illuminating from within the signifiant meaning of facts of life occurring between people, societies and nations.'

Wychowawcza rola kultury muzycznej w społeczeństwie, p. 139.

'Selflessness is the cardinal condition, the sole psychological basis upon which the wonderful phenomenon which is every symptom of art in human spiritual life could grow.'

Wychowawcza rola kultury muzycznej w społeczeństwie, p. 146.

'It is fatal to compose one’s Symphony No. 9 as early as at such a young age.'

Description: On his Etude in B major op. 4.

Source: Janusz Ekiert, Czy wiesz? Zagadki muzyczne, Warszawa 1995, Alfa publishing house, p. 83, 242.

'This music – it is a worn-out sofa.'

Description: on the common inspiration with Ludwig van Beethoven’s music.

Source: Janusz Ekiert, Czy wiesz? Zagadki muzyczne, Warszawa 1995, Alfa publishing house, p. 84, 242.

'After one of our performances, an audience member with a good-natured smile on his face came backstage. – I really liked the folk songs sung with a jazzy twist – he said with admiration. That was Szymanowski.'

Description: Mieczysław Fogg on meeting Karol Szymanowski.

Source: Janusz R. Kowalczyk, Mieczysław Fogg,

'There were few composers as susceptible to literary arousal as Szymanowski.'

Author: Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, Szymanowski a literatura in: Księga sesji naukowej poświęconej twórczości Karola Szymanowskiego, Warszawa 1964, p. 127.

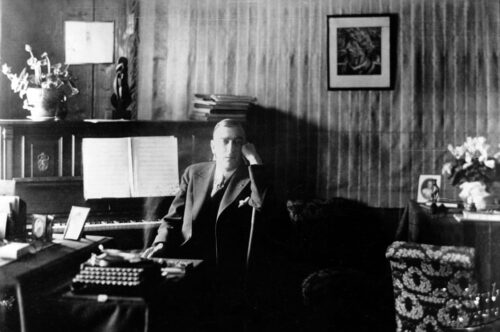

Karol Szymanowski in France, May, 1936. Photo: Studio Lipnitzki / Roger-Viollet

Each change created a new system. A dark and dense one or a bright and colourful one. A Caleidoscope of sound. Each vibration of inspiration brought new solutions.

In the first period, the solutions were rooted in late Romanticism. They gradually transgressed its boundaries yet continued to reference it. They were to be heard in the Sonata for Violin or the popular Overture in E major, as well as in the metaphysical Hymns to Poems by Jan Kasprowicz. Then, a sudden liberation: expression, yet bathed in a variety of sounds. Impressionism, yet specific for himself only – at the same time sophisticated and intensive to the point of seeming zealous, but also full of longing. These are the Mythes, the Masques, the Métopes, and the Sonata No. 3 for Piano. A moment of peak maturity. Symphony No. 3, Concerto No. 1. King Roger, the songs turning towards the Orient.

And yet another tremble: the composer moves from a source he has already thoroughly explored, and maybe even one that has run dry, to a new world. He gradually falls under the spell of the primal charm of folklore, enamored with the room it leaves for enhancement and sophistication, i.e. bringing it into one’s own domain. The Słopiewnie are gradually emerging. The Symphony No. 4, the two opuses of Songs from Kurpie, finally the Harnasie ballet and the Concerto No. 2 for Violin. The Mazurkas. The themes are twirling with oberek or shooting towards the mountaintops of the Tatras – at the same time enabling Polish music to reach its own peak. A music that sounds familiar and of one’s own, yet simultaneously cosmopolitan, at home on global stages.

From place to place, from inspiration to inspiration, from one style into another. True to his own, honest needs – without manifestos and theatrical gestures justifying with words that which the audience could not hear in the music. The sounds themselves are sufficient. A century onwards – still unchangeable.

The first bars of Karol Szymanowski’s Preludes op. 1 were enough for the young Artur Rubinstein to discover the unique and spectacular talent. A talent he instantly pledged allegiance to.

It was, however, no coincidence: soon, Szymanowski’s compositions were to be found in many excellent artists’ repertoirs. His music was first brought to international audiences by the most famous performers of the era: besides Rubinstein they were first and foremost Paweł Kochański – a violinist adored in both hemispheres – and the outstanding conductor Grzegorz Fitelberg.

The Violin Concerto No. 1, full of unexpected timbres, was also performed by the great virtuoso Bronisław Huberman, as well as the outstanding, focused Georg Kulenkampff. La Fontaine d’Aréthuse, melodic and murmuring with double trills, was, in turn, performed or even recorded by virtually everyone, including Jozsef Szigeti and the young Yehudi Menuhin. Late masters of this music were also Roman Totenberg and Dawid Ojstrach – and, naturally, all outstanding Polish violinists.

After Kochański’s tragically premature death, the Concerto No. 2 for Violin, lively and spectacular, was taken over by the exquisite Albert Spalding, performing the piece under Sergey Kusevitsky in Boston – the great conductor could not wait for the first performance to take place in America.

The 4th Symphony was performed by the composer himself (and every pianist ought to listen to the surviving fragments of the interpretation!), with Jan Smeterlin including it into his repertoire immediately and Artur Rubinstein a little later. The 2nd Sonata was first struck with Rubinstein’s, a young man at the time, own fingers, further to be taken over by Heinrich Neuhaus and his Moscow students, predominantly Svetoslav Richter (alongside the 3rd Sonata).

Thus, Szymanowski’s music was not unknown – yet it fell prey to history. First, it was erased from memory by the war – the composer had died short before its outbreak, in 1937 – and after it had finished, contemporary music was assigned new duties. It was then that the problem of entirely mistargeted promotion appeared. People’s Republic of Poland was trying to sell its outstanding recent composer as – a matter of course – predominantly a folklorist. Therefore, given the post-war contempt for the style, the world had to rediscover Szymanowski independently, without the participation of state-run cultural agencies. What was needed for such a rediscovery to occur were both time

and the right piece. Thus, the renaissance began with the erotic mysticism of the King Roger and conductors seeking new repertoire: Charles Dutoit and Simon Rattle. Today – three decades after reappearing – Szymanowski’s music has become standard repertoire for soloists, orchestras, conductors and theatres.